Total Contact SaddleI purchased my TCS in November of 2019. I have been using it on a wide range of horses since then. I understand the skepticism around the TCS because it does not adhere to traditional saddle fitting rules. What you need to understand is that it's not a traditional saddle. Saddles were designed for the comfort and convenience of the rider- to help riders stay seated in battle, strong enough to support the weight of a rider and their weapons. Saddle trees were designed to accommodate a seat for the rider to sit in and protect the horse's back from it. Because trees are hard, rigid structures made from materials like metal, wood, and fiberglass, a sufficient channel is necessary to keep the tree off the spine and the nerves that run along it to prevent soreness. The TCS does not have a hard inner structure that needs to be kept off the spine. The long back muscles attach to the spinous processes, so even when the weight bearing surface of the saddle sits on these muscles, the spine is still bearing weight. So the idea that the spine should not bear any weight is silly, when any weight on the back will put weight on the spine as well. The spine is not floating in your horse's back, it is attached to the muscles our saddles sit on and therefore bears weight too. The idea of spinal clearance is not about keeping weight off the spine, but keeping hard, painful structures off these sensitive areas to avoid causing soreness to the bony spinous processes and prevent the hard edge of the tree from interfering with the nerves that run along the spine. Ideally with treed saddles we want there to be even contact with the horse's back along the length of the panels to avoid concentrating pressure to small areas. Again, why? Because trees are made of hard, inflexible material and when they dig into the soft tissue of your horse's back they can cause pain, bruising, and soreness. The Total Contact Saddle does not have a tree that we must protect the horse's back from. It's not the rider that the horse's back needs to be protected from, but the saddle and tree itself that was designed for the comfort of the rider. With the TCS, the rider's weight is dispersed through the stirrups, the surface area of the saddle, and the rider's seat and thighs. As long as you have a little padding to protect the horse's back from your seat bones, that is really all that is needed. It's like riding bareback with stirrups. People rode with literally a cushion, a set of stirrups, and animal hides for padding. It was very minimalistic like the TCS. It wasn't until people wanted to carry swords and bows and arrows, and not be knocked from their saddles during battle that we started getting pommels, cantles, and trees. Northern Plains Pad Saddle with Buffalo Skirt and my TCS with Reindeer Hide. Not dissimilar. If you're still worried about the lack of scientific evidence to back up the TCS, just know that you don't need a peer reviewed study to be able to tell if a saddle is causing problems. Many people will claim that the TCS will cause long term back issues and damage to the spine from one look at it, disregarding that my horses and many others have been ridden in the TCS for years and are checked regularly by equine professionals like vets, chiropractors, and bodyworkers. In addition to this, my horses are routinely palpated by myself to check their backs after rides. Not only do their backs check out perfectly during professional evaluation and my own palpation, but my horses do not show any adverse reactions to the saddle when I tack up like many back sore horses do when they see someone approaching them with a saddle, my horses voluntarily line up at the mounting block for me to get on, and they move forward willingly and freely under saddle. If this saddle was going to cripple my horses or cause long term damage to their backs, I would know by now. I appreciate your concern, I acknowledge that this saddle does not adhere to traditional saddle fitting rules, but please understand I have firsthand experience with this saddle and accept that my horses are fine. I would have quit using it long ago if it hurt them. Here is a user guide I have compiled for the TCS for anyone interested. Total Contact Saddle - This video is an introduction to the TCS. It shows the saddle and what type of stirrups and girths work with it. Total Contact Saddle FAQs - This video answers a lot of common questions about the TCS. Total Contact Saddle Padding Setups - This video shows a few different padding setups that I like. Total Contact Saddle - How you can tell if your horse may be experiencing back pain.

0 Comments

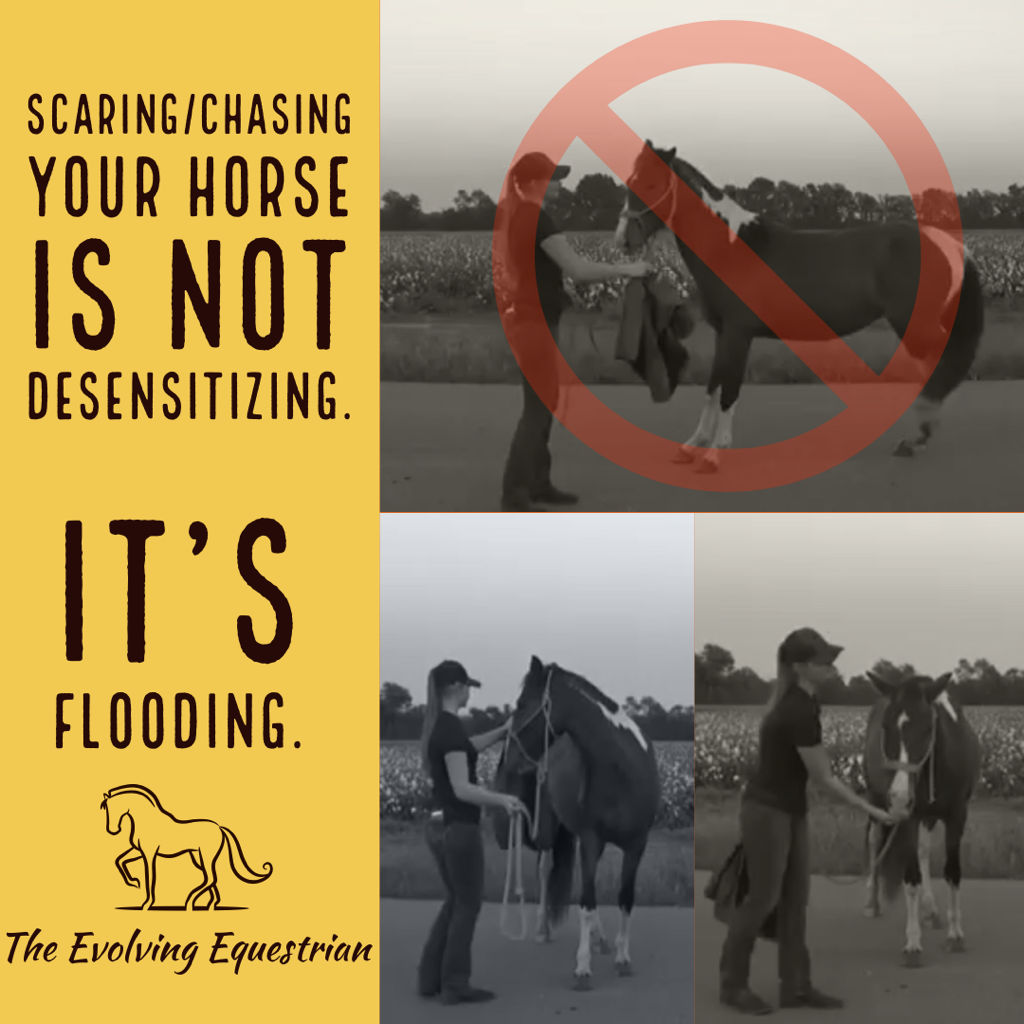

Scaring your horse is not the same as desensitizing. Chasing your horse around with something he finds scary is also not the same as desensitizing. Trainers who recommend you give your horse a heart attack or act crazy around them to get them desensitized do not understand the correct definition or process of systematic desensitization. Teaching horse owners to continue applying a scary stimulus until the horse shows “a sign of relaxation” after the horse has acted on his fear by moving away or acting fearful, is also an incorrect approach to systematic desensitizing. This actually falls under flooding, not desensitizing. A horse is considered over his fear threshold when the stimulus is at a strong enough intensity and causes a reaction. Shying, bucking, bolting, rearing are very obvious indicators the horse is well over threshold, but the horse is *first* considered over fear threshold when he initially acts on his flight instinct by moving away from whatever he finds frightening. It may be a step backwards or sideways, but if it is a retreat from a scary stimulus, it means the horse is not comfortable and has moved into flight mode. Big reactions aren't the only sign your horse is over threshold. Something as small as a step back can tell you everything you need to know about how your horse is feeling. It's when we ignore these smaller signs that they turn into the big ones. A horse who raises his head, widens his eyes and tenses up is considered at threshold- not over because the stimulus has not yet reached an intensity to cause him to react on his instinct to flee. If you notice any of these signs, back off! Reintroduce the stimulus by starting further away, with less intensity, and for a shorter period of time. Forcing a horse to accept a stimulus at an intensity he is not comfortable with is called flooding. Flooding is a technique where the learner's senses are overwhelmed with a stimulus they may find frightening as a form of desensitizing. The stimulus is inescapable, meaning it does not cease and the learner cannot get away from it even if he is uncomfortable with the level of intensity. Imprinting foals is a common form of flooding. The foal is pinned down on the ground and the handler touches the horse all over, rubs him down with plastic bags, puts their finger in their mouth, etc. The foal may struggle, but the handler continues to expose the foal to whatever he's doing. In studies done on imprinted foals vs foals that were not imprinted, there was no significant difference in their behavior during handling at a later stage. Which is very interesting and very telling. We have all been taught that if the horse moves away in fear we have to keep the stimulus the same because if we give him a "release", he will learn to run away from whatever we are trying to desensitize him to. We have to keep going until the horse stops moving and shows “a sign of relaxation.” This is false. When a horse moves away from a scary stimulus, he is in flight mode/above threshold and is incapable of learning or retaining information. By following or "drifting" with the horse as he moves you are also, unknowingly increasing the intensity- in the horse's mind, now the scary thing is chasing him. This is when things get ugly fast. Jogging after the horse as he runs backwards ensues and it takes quite a while for the horse to come back down below threshold. When the horse finally does stop, it is usually due to learned helplessness and the “sign of relaxation” is actually a displacement behavior. This is all misconstrued as the horse accepting the scary stimulus when in actuality, the opposite has happened. The horse is so frightened he has given up escape. We know that flooding is forcing a horse to accept a stimulus at an intensity that he is uncomfortable with, but we normally consider this as a horse that is physically restrained and unable to move at all. This is not the case. If the stimulus is inescapable, even if the horse is moving, but still cannot get away from the stimulus, it is flooding. Strapping a saddle to a horse and letting him buck it out is flooding, for example. Although he is able to move, he is still unable to get away from or escape the saddle. Flooding is classified as the inability to escape not the inability to run or move. So, when a horse moves away from a flag or plastic bag and we continue to apply the stimulus by restraining him with the lead rope and following him around, we are flooding. Just imagine how well a person might overcome their fear of snakes if someone chased them around with one! Do you think this would help them overcome their fear or rather traumatize them? In systematic desensitization we are introducing a stimulus at an intensity the horse is comfortable with and slowly increasing that intensity and building the horse's confidence as well. If you send the horse above threshold, you should back off and find a better starting point. Decreasing the intensity will not hinder the desensitizing process. It will allow the horse the opportunity to come back down below threshold, where he can process and reason, instead of just panic. Ideally, we try not to push the horse above threshold in the first place. We would pay attention when he shows signs that he is at threshold- when he first takes note of something scary by the classics: raised, head, wide eyes, tense muscles and adjust our intensity, distance, and duration accordingly. I was probably ten years old the first time I saw counter conditioning. My friend had a young, black and white paint colt who was very skittish and head shy. She sat on the fence with a bucket of grain and let the horse eat out of the bucket while she petted his neck and slowly worked up to touching his poll, jaw, and face. Every evening she would sit on the fence with her bucket and touch him all over while he ate. I don’t think either one of us exactly understood the science behind why what she was doing worked, all we knew is that it did.

Flash forward eight years later and a young, skittish, black and white paint colt came into MY life. Gabriel was a yearling when he came to the farm. He didn’t have any handling and to make matters worse, he was born with bilateral cataracts, so his vision wasn’t the best. I tried to stay away because I already had two other horses and I didn’t need to get involved and attached to a third. But, after he stood at the back of the pasture without moving for almost three days after being chased off by the other horses, a fellow boarder convinced me I had to do something. I coaxed them in from the field with a bucket of feed. When I got them up into the paddock by the barn, someone suggested I use her horse to lead them into the barn. It worked. From there, I stalled my horse beside the black and white paint colt. And after they had some time to get to know each other over the stall, I led my horse with the baby following to a smaller field where they could be by themselves. I couldn’t touch the colt. He wouldn’t let me pet him or halter him. So, I did what my friend had done with her colt all those years ago. I sat on top of my feed bin and held a bucket of feed. He started coming up to eat out of the bucket and when he was used to being close to me, I started petting his neck, and up towards his poll, and eventually his jaw and face. I did this everyday until he was no longer afraid of me. It wasn’t long after I got the colt gentled down enough to catch and halter that I got into Natural Horsemanship. I attributed much of my success with this horse to the program I followed, but I wonder, would I have ever been able to touch the little guy if it weren’t for counter conditioning? Counter conditioning is pairing something the horse doesn’t like with something he really loves to change their association from a negative one to a positive one. In this case, touch was what the horse did not like. He was afraid. Touch=fear By me holding the bucket for him to eat while I petted him, he learned that touch=food. This is counter conditioning. It is a great way to change bad associations with objects, experiences, places, behaviors, people, etc. to good ones! When it comes to eliminating undesirable behavior, you have three choices.

1. Administer punishment. Positive punishment is adding an aversive following an undesirable behavior to decrease its occurrence. The horse learns that performing that particular behavior results in a bad outcome. The complications of using punishment is that while it does create a negative association with the response in order to diminish it, this association is also carried over to the handler, and to learning. Punishment causes the horse to be nervous and creates refractory behavior towards learning. Because of this, punishment should be your very last choice. Unfortunately, many horse owners and professional trainers don’t realize that their training is made up of a lot of punishment disguised or mistaken as pressure and release. Punishment does not solve the root of the problem, it simply suppresses behavior. This makes relapse a common occurrence in horses trained with a lot of punishment. The leaner only suppresses the behavior in the presence of the punishers. Once they are removed, the behavior will persist. A horse who refuses to load and is made to work as consequence for balking, will only load when the handler is holding a whip and standing in position to correct the horse if necessary. Basically, once the threat of punishment is not in place, the undesirable behavior reappears. This is because the root cause, fear of the trailer in this example, was never truly addressed and overcome. 2. Ignore the behavior. In theory, behavior that is not reinforced will decrease. Simply ignoring incorrect or undesired responses can work to eliminate them. For example, many horses try to reach for the treat bag when people first begin using food rewards in training. Ignoring this behavior will actually make it stop. The horse will learn that reaching for the food is never the response that gets them the reward, so they are less likely to continue doing it. Ignoring unwanted behavior can be an effective way to reduce it. If a behavior is maintaining or increasing in frequency it is being reinforced. When we ignore undesired responses, the horse learns it doesn’t work for him because it does not result in reinforcement. 3. Train an incompatible behavior. Training an incompatible behavior is by far the most proactive way to eliminate undesirable behavior. Both punishing and ignoring unwanted behavior do nothing to teach the horse what behavior(s) you do want or which ones will result in reinforcement. Using positive reinforcement to teach the horse what to do instead is a much better alternative. If your horse drags you when you are trying to lead him, you could yank on the lead rope to teach him that behavior equals pain/discomfort. You could ignore it, but if the horse gets where he is going faster, he may still find dragging you reinforcing. The best choice to eliminate the behavior of being pulled by your horse would be to teach the horse to stop and stand on cue. Personally, I would begin without a lead rope and teach the horse to stop on whoa at liberty. Every time I stopped and said whoa, and the horse stopped with me, I would give him a food reward so he learns that stopping equals food. Once my whoa was solid in a controlled environment without the halter and lead rope, I would try it on line. Now that the horse knows that stopping will earn him a reward, he will be more likely to stop and pay attention to me than take off with me skiing along the sand. Every unwanted behavior does not need to be punished. Often times not reinforcing it by ignoring it is enough to make it decrease. In the times when its not, training an incompatible behavior is a lot more effective and ethical choice than administering punishment. Punishment is the most used and abused quadrant, not just in horse training, but in our society in general. If we don’t like something, we know to punish it to make it stop. People spank or whip their children. Fines or citations are issued for traffic violations. We are most familiar with punishment. However, there is more to behavior modification than punishment. It’s not the only answer. It’s not a necessity. From what you have heard about bitless bridles, you might think that removing your horse’s bit is the solution to all your problems. And for many horses, it does make a huge difference. The horse shows less stress and in turn is more responsive. So, you decided to give it a try with your horse and it wasn't quite the dream ride you were hoping for. Your horse ran away with you. You felt like you had an overall loss of control. Your horse was not responsive to your rein aids. Does that mean that your horse has to have a bit? Does bitless just “not work” for some horses? You might have been told that your horse has a hard mouth. Are “hard mouthed” horses not able to go bitless?

Horses that are described as having a hard mouth do not have anything wrong with them or their mouths. Some horses have higher levels of sensitivity which naturally makes them more responsive to bit pressure and other horses are just naturally a little duller. They require more pressure to produce a response. Poor training can also create horses who are not quick to respond to light pressure. Pulling unnecessarily on the horse’s mouth can teach the horse to ignore the pressure because it doesn’t mean anything. There is no response that he can offer that will cause the pressure to go away, and so he learns to just live with it. While there are many reasons that a horse can develop a hard mouth, it doesn’t mean you are stuck with an unresponsive horse forever. The problem that riders run into when they try bitless is that the aversive has been minimized. If your horse requires a strong aversive to produce a response, you may not be able to apply that level of pressure with a bitless bridle, because many gentle bitless bridles are inherently milder than bits. It is much the same as a horse who is accustomed to being ridden with spurs being ridden with a bare heel. It is difficult to get the horse to move or respond to the leg aids, because you do not have any means of escalating the pressure/aversive. Is there no help then for your horse? Does this mean you will always need a bit? Nope! This is where positive reinforcement/clicker training comes into play. In positive reinforcement, the motivation is not aversives. That means the horse is not working to avoid pressure, he is working to earn something he likes. This is a real game changer for heavy, dull, unresponsive, or hard mouthed horses. The motivation for stopping when using aversives is finding relief from the discomfort or pain the bit causes. Some horses learn easier than others that if they stop upon feeling light pressure, they can avoid the escalation or stronger application of pressure. Other horses take longer to learn this and some always require a stronger level of pressure. However, the motivation for stopping when using appetitives, is the addition of something the horse wants. This increases the horse’s motivation. With pressure and release or aversive only training, the horse will put in the minimal amount of effort required to avoid the aversive. They are not inspired to try very hard. However, when you add in something that they value, suddenly the horse is more engaged and their try has been boosted. For example, you might begin on the ground with your horse wearing a halter and lead rope. As the horse is walking along beside you, say whoa, stop walking, and apply some very light pressure to the halter as a tactile cue (a cue that can be felt). When the horse stops, I use a bridge signal, a click or the word “yes” will suffice, and then give the horse a food reward, like a few alfalfa pellets or a handful of their feed. Soon, the horse will learn that if they stop on your cue, they will get the food. As the horse becomes more solid, you can begin to fade the food rewards out, so that you are not feeding every stop, but only the really nice ones. After you have taught your horse how to stop on cue on the ground while leading, you might practice while lunging, that way the horse knows the cue in all three gaits. By the time you are ready to ride your horse, you will have a transferable cue that your horse already understands and happily responds to. This concept is the same as far as turning, half-halts, and downward transitions go. Mark the response you want to reward with your bridge signal and follow up with a food reward. I recommend teaching the horse to come to a complete stop first for safety reasons and so your horse understands the correct response to the rein aids. It is very easy to get downward transitions and half-halts when your horse has a good halt in place. There is a lot of free information available today about positive reinforcement and clicker training. If you’re struggling to transition from bitted to bitless, I encourage you explore this approach because it really is a game changer in many ways. Don’t get discouraged if your horse doesn’t transition beautifully to bitless the first time you give it a go. It just might take a little extra training to help him understand. It is the same idea when someone recommends a bigger or stronger bit for a horse that ignores the rider’s hands. Most people are quick to point out that the horse needs better training, not a stronger bit. And they are correct. If you are having a hard time trying to go bitless, your horse just needs a little more training and a different form of motivation! “Don’t I have more control with a bit?”

“Aren’t I safer riding with a bit?” These are common, valid questions that many riders ask when considering switching their horses to a bitless bridle. We think that bits give us more control over our horses and that control also makes us safer riding with a bit than riding with out. But, are we correct in this thinking? Unfortunately, if you are relying on a piece of tack to control your horse or keep you safe, your trust has been misplaced. At the end of the day, we still ride creatures that weigh a thousand pounds and have a mind of their own that is wired to escape any perceived threat by whatever physical means necessary. If the animal decides they’re out, what you have in their mouth will do little to stop them. I was restarting a mare that had been put out to pasture for a few weeks. She had never given us any issue when we first started her and was pretty solid when we gave her some time off, so even though she bucked when I saddled her up and lunged her, I just thought she was fresh, had gotten it out of her system, and would be safe to ride. I was sorely mistaken when I got on her back. She bucked around the arena with me desperately pulling on one rein trying to bend her head around and get her shut down. It did not matter how hard I pulled, at what angle, or anything. She was terrified of me, the saddle, everything. I rode her around the arena for two laps while she bucked and finally, I gave up and bailed off onto the fence on the way by. This is just one example of not having control or being kept safe by riding with a bit. She was in a twisted wire snaffle bit. Not the most gentle nor the most severe bit, but truthfully, nothing would have stopped her that day, not even the harshest bit. I failed her in my training and judgment that day. The bit had nothing to do with it. What would have kept me safe that day and given me more control would have been slowly reintroducing the saddle and only getting on her back when she was comfortable with the saddle and cinches first and then making sure she was also ok with me up there. The bit and attempted one rein stops did nothing to help me. If you believe you are safer because you ride with a bit, you have a false sense of security. Often, grabbing up a handful of reins when your horse is scared can add to their fear and only make a bad situation worse. Not only are you adding pressure or discomfort to their mouths, but fear of being restrained or trapped when they already don’t feel comfortable and want to get away. With the little mare I was restarting, my one reins stop attempts only strengthened her desire to escape me because I was trying to stop her when she only wanted to get away. She was frightened of me, and me pulling on her felt even more like an attack. I was given an unstarted paint colt when I was twelve years old. I backed him myself and he had a funny personality. One thing he learned to do was veer the opposite way I was steering and unseat or throw me off. He got out of work and usually if he was successful in getting me off he got to go back to the barn or closer to his friends. I always loved riding in a halter and lead rope around the pasture even as a kid, but with this horse I always rode with a bitted bridle because of his little trick. I could be cantering along on a circle tracking left, and he would swerve right, nearly pitching me over his shoulder. Riding in a bit made it easier for me to try and discourage this behavior, but when he committed, it didn’t matter if I was riding in a halter or bit- I could not physically stop him from doing it no matter what piece of tack I was using. I actually still own this goofy paint, and since I started clicker training, I have finally been able to resolve this problem. You see, the issue was never about strength or force. It was about a lack of proper training. Chance didn’t want to stay on the circle because going back to the barn or back to the other horses was much more reinforcing than toting me around. When I began to reward Chance for listening to my rein aids, allowing me to guide him, and going the direction I asked, even just for a few steps BEFORE he decided to throw the duces, he learned that staying on the circle was reinforcing. Once there was something in it for him, he was a lot more willing to comply. Training was the solution, not a bit. If you are holding your horse together with a bit, you already lack control. Preparation through training and proofing are the only way to prevent unsafe situations from occurring in the first place and have control. The only way we can control a thousand pound animal is through their brain. Any attempt to physically control a horse is futile and foolish. The idea that a bit can do this by the amount of pressure/pain/discomfort it inflicts or the strength of the rider is as equally silly. Bits only work in the first place because of the training behind their use- not the tool in and of itself. You would be safer and have more control riding without a bit if you have taken the time to properly train your horse than you would riding a poorly trained bitted horse. When it comes to safety and control, I have learned that my trust is better placed in my training than in my tack. #horses #bits #bitless #horsetraining Bits are inherently aversive. Hackles are raised whenever I tell someone that, but no matter what sort of emotional response that statement evokes does not change the fact. Whether you choose to use a bit or not... actually, ESPECIALLY if you choose to use a bit, you need to understand the bit is an aversive.

Most people do understand and accept this, but you would be surprised at how many folks will argue that they're just "massaging" their horse's tongue or "vibrating" the reins as though the bit is some sort of pleasurable means of communication. It's not. And whatever your personal convictions are about how ethical bits are- it's important to be completely honest and fully understand about how this tool functions in order to: A. Make an educated decision on whether or not to use it. B. Use it properly if you choose to. I'm not here to guilt anyone into ditching their bits. I'm here to provide you with facts, so you can make your own decisions and understand how I've come to the conclusions I have. To each their own and I truly mean that. Back to bits. Any training technique or piece of equipment functions one or two of four ways. There is nothing new on the market and there will NEVER be anything new. What? Why!? Because organisms learn through four different ways. No more and no less. It's the laws of science and it hasn't and won't ever change. Any device or technique we apply, (if it works) will be classified as positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, or negative punishment when dealing with voluntary responses. If you've heard me chatter on about this in any of my other posts, you'll know that these are the four quadrants of operant conditioning. Train your horse, train your dog, your cat, or your husband with them- it works on every species. (I've experimented with all of the above. Still a work in progress with the last, albeit!) Bits fall under the category of negative reinforcement and positive punishment. Think of the negative and positive as - and + because you are either subtracting something or adding something as reinforcement or punishment. It does not mean good and bad. So, when we use a bit, typically, we pull back on the reins and when the horse does our bidding we quit pulling. We are subtracting the pressure of the bit to increase the chance that the next time we pull back he will perform the same response to find the relief again. That means we are using negative reinforcement. Even if you pick up with just two fingers on the rein, the pressure is uncomfortable or annoying at best: it causes the horse to search for relief. This is an aversive. This is why negative reinforcement is also known as "avoidance learning". The opposite is an appetitive. One is something you avoid; the other is something you find pleasant. A bit is never pleasant. It operates off pain/discomfort and is inherently aversive. Now then, one more example. If you ask your horse to stop and he doesn't, so you give a sharp tug on the reins- you are using the bit as positive punishment. You are adding an unpleasant stimulus to decrease the chances that he will ignore your cue the next time. I prefer to educate my horses mainly by using appetitives these days. They learn easier and faster, they enjoy it more and are less stressed doing so. I teach my horses how to respond to my cues without using aversives and since bits are aversive, I haven't had a need for them since I started using +R. So, it didn't really come down to whether bits are humane or ethical for me. That's up to each one of us to decide for ourselves. Bits just became unnecessary for me in my training. I have found in my personal experience that horses learn better and are more responsive without a bit. The bit does inflict pain at times. A bit is very uncomfortable for a green horse and just the act of packing a bit around can be enough to put a greenster at threshold, let alone trying to teach him anything by actually using it. Furthermore, the way a bit functions through negative reinforcement, is a guessing game sort of process for the horse to learn what the correct response is in the beginning. When you first apply pressure to the bit to teach the horse to stop, automatically he will do the opposite- he'll resist the bit and speed up, which is the horse's natural response to escape when he is frightened or something is hurting him. We have to allow the horse to explore his options before we can release to the correct response. He may continue forward, he may run sideway, he may toss his head and pull on your hands, all before finally stopping and then we can release. I have dealt with a host of sensitive and hypersensitive horses and this process of trial and error to figure out the correct response really stresses them out. This is because fear and pain are not very conducive to learning. On the other end of the spectrum, I've also dealt with my share of laid back horses and they simply don't have the energy to put forth to figure out what the heck we want and so they stop trying and are labeled stubborn or hard headed. I much rather explain to my horses exactly what I want to take the guess work out of it. It preserves the horse's try and keeps them in a relaxed state so they can engage and learn. These are the main reasons I've come to the conclusions I have. I do believe horses are physically better off bitless as this video shows. It highlights some things we may not realize or have chose to ignore about the way bits act inside the mouth. I hope at the very least when people watch this video, they understand the amount of pain they can inflict on their horses and try to be as gentle as possible when riding with a bit. I'm not proud to admit that I have banged on horses’ mouths because I was taught they were hard mouthed and I had to get my point across. That is sorely incorrect, unnecessary and unfair to the horse. If a horse does not respond to an aid it is because he has not been taught properly, not because he is resistant or stubborn. It falls back on the rider. It’s our responsibility to educate the horse and if we are met with resistance it is an indicator that we have not not fulfilled that responsibility. If we must use pain and force to coerce the horse into doing our bidding, can we even call ourselves trainers? The first evidence of the use of bits dates back to 3500-3000 BC. Metal bits came on the scene between 1300 and 1200 BC. Have we not evolved in our training since then? https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=gi57PsjIFqM There are some riders and trainers who I have a lot of respect for. I hold them in high regard. I admire them. I also have “respect” for an electric fence. Does this mean that I admire the fence or think highly of it? No. I don’t respect the fence in that aspect, it is more a healthy dose of fear than it is actually respect. Is it really respect that we want with our horses or is it a certain level of fear?

Let’s be honest. We all know that horses aren’t capable of respect as it’s defined. Respect is to admire someone or something deeply as a result of their abilities, qualities, or achievements. Horses can’t/don’t admire us because of our ability to chase them around a pen or move their feet forwards, backwards, left, and right! I think deep down, we are aware of this fact. The truth is respect has been redefined. Respect has been used in place of the word fear because it has a nicer tone. Fear means to be afraid of someone or something as likely to be dangerous, painful, or threatening. So, do I admire the electric fence, or am I afraid of it as likely to be painful? Definitely the latter! I don’t respect the electric fence, I fear it. Likewise, our horses don’t respect us, they fear us. We say things like, “I want my horse to respect my personal space.” Are we saying I want my horse to admire my personal space or do we really mean we want the horse to be afraid of entering our personal space as likely to be dangerous, painful, or threatening? “I want my horse to respect the bit.” Do you want your horse to admire the bit? Or do want your horse to fear it? Unfortunately, fear fits the description of what we want much better than respect. But respect just sounds so much nicer! When a horse moves away when we swing a stick at him, some count it as respect, but again, it is not the horse’s admiration of our ability to swing the stick that is causing the response or “respectful” behavior. It is the horse’s fear of the stick. Respectful means showing deference or respect. Fearful means feeling afraid, showing fear or anxiety. Is the horse showing deference when he moves away from us when we swing a stick? Or is he showing fear? He’s showing fear by moving away. You may have heard before that the horse's brain is not capable of respect. If we are being real, it’s not respect that many are after anyway. What some want is for the horse to be a little bit afraid. And its well known that horses are capable of fear. So, are you actually gaining your horse’s respect or are you really just putting some fear in him? I’m not here to convict or convert. I just want to bring some honesty to horse training since there seems to be quite a bit of sugar coating going on. Whatever you do with your horse is up to you, I just want you to have the truth. It's yours to do what you want with. Do horses want a leader?

Maybe you have heard that horses want a leader. That they crave the type of security that a good leader gives them. Maybe you have been told that horses don’t really want to be the leader themselves and that they would rather someone else step up into that role for them. If there is no one willing to take on that role, then the horse will have no choice but to be the leader himself, despite the fact that he would rather not. What can be confusing in the horsemanship world is that as many times as we have heard that our horses just want a leader and preferably not themselves, we have also heard that we have to gain their respect and prove ourselves as capable leaders. Well, which is it? Are horses natural born followers, that willingly submit themselves to whoever is brave enough to step up to the plate or do they constantly challenge authority? This is what happens when we anthropomorphize horses. People end up confused and with a lot of misinformation to sort through. However, because it appeals to the human’s way of thinking, it “makes sense” and is easy to believe, but is it actually correct? From childhood, we understand ranking. We know that our parents call the shots and that they are the leaders and we the followers. At school, we learn to listen to the teachers because again, they are the leaders. At work, we have a boss and we understand where we fit in in the chain of command. Naturally, we apply these principles to the horses in a herd and in turn, to our relationship with them. Have we gotten it wrong? Yes, and on many levels. First, in order for a horse to desire a leader to begin with, he must be able to understand the concept of rank. This would mean that horses have the mental ability to understand where their position is in relation to the other horses in the herd. Equine cognitive studies suggest that this is not likely. Each horse has an individual relationship with each other horse in the herd, they interact with each other on a “bilateral level”. They do not see the whole picture. They do not understand an order of rank. This alone, should be convincing enough information that horses don’t “want a leader”- they don’t view other horses or themselves as leaders or followers, or even understand where they fall in the “pecking order”. It is beyond their capabilities. Social hierarchy is a man-made concept. Second, conflict usually only arises when resources are scarce. This suggests that these competitions are more about retaining resources than working their way up the ladder. One horse may have stronger resource holding potential over hay than he does over the best spot in the shade. Why is this? If there was a single, clear, leader or “dominant”/”alpha” horse, shouldn’t this be the same horse no matter what? How come one horse who is the winner in a competition over a spot at the round bale, is the loser to a lesser horse when there is conflict over the shady spot? We often just attribute this to subordinate horses wanting to challenge the leader and move up in the ranking. But actually, it has little to do with dominance or rank, and is actually about what resources are important to the horse. If the shade is not worth it, he may submit easier than if he is hungry and really wants some hay. With horses, it is very simple. It is about survival and nothing more. First, survival of the individual and second, survival of the species. Adding much on top of that complicates things more than what they really are. Horses are unconcerned and unaware of a social hierarchy. They are want what they want in the moment. These competitions predict the outcomes of similar future situations between two horses, but is again on a bilateral level. Each individual horse knows based off prior interactions, the outcome of such contests with each other individual horse. He does not see himself as at the top, middle, or bottom rung. He sees himself as either the winner or loser of whatever resources, not the dominant or subordinate nor the leader or the follower. Third, if horses wanted a leader to follow, only the dominant horse would lead. Seems obvious right? However, movement initiation has been studied extensively and research has found that any member of the herd can be a leader. This means that the top horse or one horse does not always lead. Kind of blows the whole theory apart, doesn’t it? In fact, even horses that we might consider to be at the bottom of the pecking order, can lead the herd. How is this? What determines this? The animal with the greatest need usually initiates movement. It is not the most dominant horse or a single leader that tells the herd when and where to go. The thirstiest horse, regardless of where we might say he falls in the ranking, heads for the water. Because of synchronization within the herd, they all drink at the same time, they all eat at the same time, they all become thirsty at the same time. When the other herd members see the first, thirstiest horse heading for water, they follow because they too, are thirsty. Not because their leader bids them. There is nothing more complex about it. Finally, even if it were so that there was a single leader that came out on top in every conflict, led all the other horses all the time, and even if horse’s brains were capable of understanding and mapping ranking, there is no evidence that they view us as part of their social system. We are not the same species. Have you ever seen your horse try to incorporate any other animal, say a dog, into their herd? Never! In fact, what do they do when approached by another species, predators in particular? They run! What makes us think that the horse would ever decide that they want to “follow” us? Or that they want us to be their leader? It is rather absurd. No matter how hard we try to imitate their behavior, it doesn’t change the fact that they are horses and we are humans and they do not view us the same way. Can you have a great relationship with your horse? Can you have a great partnership? Can you build trust and confidence? Of course you can! But selling the idea that horses want a leader is not the way to go. Horses want food, water, and other horses. They aren’t waiting for someone to come push them around and show them what a good leader they are. They are just out there living their best lives. How can we fit into it peacefully, is the real question. https://www.academia.edu/17520909/Movement_initiation_in_groups_of_feral_horses https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/18569224/ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0737080617300059 https://thehorse.com/132977/dominance-human-horse-relationships/ This past week I've had a lot of great conversations with several people about respect and dominance in horses. Understanding the facts is what changed my entire perspective on horse training.

Like so many, I learned from an early age that the horse was to be subservient to his rider. I was taught to be the boss, to make the horse listen and not let him win. Then, I learned about gaining the horse's respect and communicating through body language to mimic the dominant, lead horse's behavior. I was taught that horses need and want a strong leader within the herd and within the relationship of horse and human. That we have to prove our ability as such a leader since they depend on one. I was taught that if a horse misbehaved it was due to a lack of respect. Later, I learned otherwise. I learned that horses don't possess the brain structure like people do that makes them capable of comprehending the concept of respect. I learned that leaders in horses can be any member of the herd, not just one, dominant horse. I read studies on movement initiation and how the animal with the greatest need led the other horses, not the most aggressive or "dominant" horse. I learned that all confrontation we see amongst horses is resource guarding. I learned that all behavior is motivated by punishers and reinforcers. That while once horse may be on the receiving end of negative reinforcement, the other is on the receiving end of positive reinforcement. I learned that respect and dominance were completely irrelevant to my interaction with horses. What I had been taught was all opinion based- not factual. The horses I worked with held me in no higher regard than they do an electric fence. They don't look to the fence as their leader, they don't try to incorporate it into their social system. They learn to behave a certain way around the electric fence because of operant conditioning not respect or dominance. If they touch the fence they get shocked: +P at work. I realized the same goes for me. I got the results I did and horses behaved around me the way they did not because my horses viewed me as their leader or respected me, but because of the way I used punishers and reinforcers- just like the fence. I was no more apart of their social system than the fence in their pasture! It wasn't hard to let go. The evidence was there and I simply closed the chapter on it and dove in to the next. Once I understood that behavior was only influenced by punishers and reinforcers it all became so much clearer, easier and more productive. I let go of pride for lack of a better word and considered the horse as he truly was-not through the flawed lenses of human perspective. When I learned that +R helped horses learn faster and easier I went that route. With dominance no longer playing a role in my training I was free to do whatever the horse needed. I was no longer obligated to present myself as a strong, unforgiving leader who demanded respect. I could be the gentle teacher who sought to help her pupils succeed. It worked even better. Here are some of the scientific articles that proved very influential to me. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0737080617300059 -Dominance Theory https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/18569224/ - Roundpen Training http://www.thehorse.com/articles/39606/dominance-in-human-horse-relationships -Researchers Elke Hartmann, PhD; Janne Winther Christensen, PhD; and Paul J. McGreevy, BVSc, PhD, MRCVS, MACVS (Animal Welfare), Cert CABC, Grad Cert Higher Ed, report that; “there is no evidence that horses perceive humans as part of their social system.”1 Dominance is not a Substitute for Learning Principles Dominance is not a satisfactory substitute for a working knowledge of science-based learning principles. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/76bf/d0c327572418589b35ba577dae85bf7449df.pdf - Movement initiation in groups of feral horses http://equitationscience.com/equitation/position-statement-on-the-use-misuse-of-leadership-and-dominance-concepts-in-horse-training - "In no case is an animal activity to be interpreted in terms of higher psychological processes�if it can be fairly interpreted in terms of processes which stand lower in the scale of psychological evolution and development." – Morgan, 1903 |

AuthorChrissy Johnson shares her personal experiences and lessons learned training horses with reward based methods. Archives

July 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed