|

Save the unicorns! 🦄

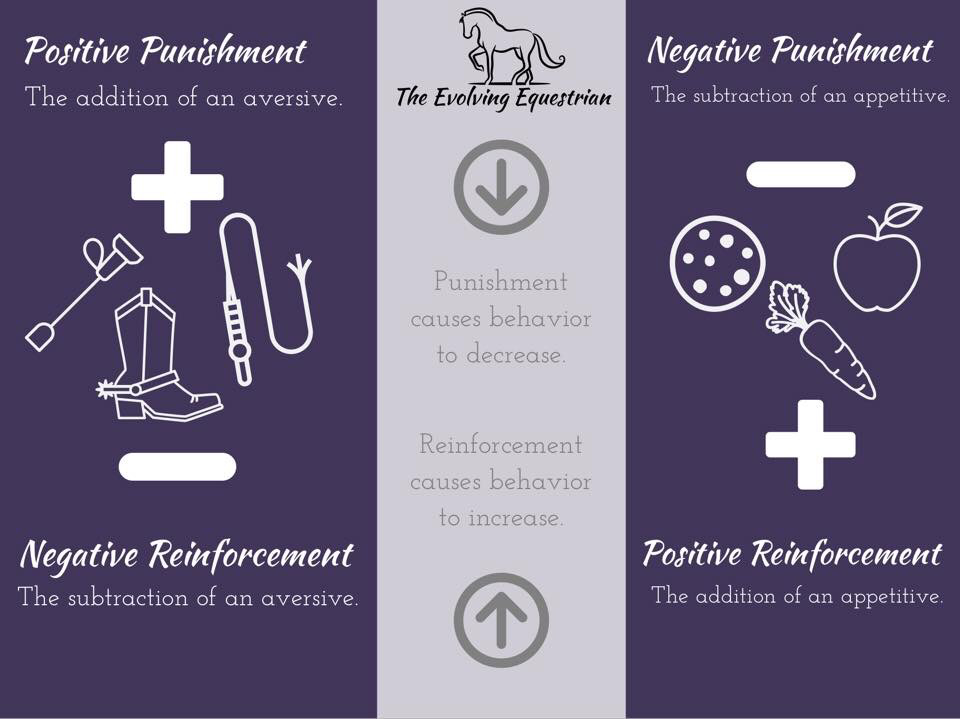

Understand the quadrants of Operant Conditioning! And remember: It’s science! 🧫🧪🧬 *An aversive is something a horse doesn’t like. *An appetitive is something a horse likes. 1. Positive Punishment Adding something the horse doesn’t like to decrease a behavior. Example: The horse paws the ground while tied, so Susie smacks him on the shoulder. 2. Negative Punishment Taking away something the horse likes to decrease a behavior. Example: Greg walks away with the bucket of feed when his horse bangs on the stall door. 3. Negative Reinforcement Taking away something the horse doesn’t like to increase a behavior. Example: Kate stops pulling back on the reins when her horse comes to a halt. 4. Positive Reinforcement Adding something the horse likes to increase behavior. Example: Kevin gives his horse a treat when he comes to him in the field. ✨We like to use mostly postive reinforcement because we want our horses to learn what behaviors we want to see more of and we want them to be happy while they’re learning them!

1 Comment

How do horses learn? Like any animal, the horse learns through operant conditioning. Operant conditioning is the learning process by which behaviors are modified through reinforcements and punishments. Operant conditioning was studied by a psychologist, B.F. Skinner, in 1938. Learning happens from day one, beginning with the foal learning to stand and nurse and it all happens through operant and classical conditioning. It is a science based approach to training.

It is important to understand the quadrants of operant conditioning so we know how behavior is modified. All interaction with horses is-is behaviors. So what is reinforcement and punishment? Let's start with the most commonly known quadrant: pressure and release, which is called negative reinforcement. Negative (-) means you are removing or subtracting an aversive stimulus as reinforcement for a behavior. For example, when you ask your horse to stop, you pull back on the reins and when he stops moving, you relax the reins. The aversive stimulus is the pressure of the bit from the reins, the response of stopping is being reinforced because the discomfort in the horse's mouth went away when he stopped. In -R you are trying to increase a behavior. The other type of reinforcement in operant conditioning is positive reinforcement. Positive (+) reinforcement is adding something pleasant following a desired behavior to increase the likelihood of that behavior. An example of positive reinforcement is giving your horse a treat when he comes to you when you call. The desired behavior is the horse coming to you and food is a pleasant, primary reinforcer that is added following the behavior to increase it. Many people believe they use positive reinforcement by petting the horse or saying, "Good boy!" However, if the learner does not find this reinforcing, it will not increase the behavior. Usually, petting and praise mean little to a horse. This is why we use a primary or secondary reinforcer. A primary reinforcer is something that is biologically significant to the horse such as food. A secondary reinforcer is a neutral stimulus that has gained its value through its pairing with a primary reinforcer. This is called classical conditioning. More on that later, but next we will cover punishments. Positive punishment can be used to decrease undesirable behavior. An aversive is added (+) following an undesirable behavior. The horse learns to associate that behavior with a negative consequence and refrains from performing the behavior again. For example, if a horse crowds you, if you smack him on the neck, he will learn that getting to close results in getting smacked and will soon stop crowding. Punishment should not be used as a primary training method because it does not help the learner to figure out what the correct response or behavior is. It only tells the learner what not to do, not what to do. When punishment is used too much and is mistaken as negative reinforcement/pressure and release, many horses will appear uninterested, disengaged or shut down. This happens because many responses the horse has offered were punished so he quits offering any at all, since he has equated his offering a response with an aversive. Many problem solving methods such as trailer loading, buddy and barn sour solutions, tying, etc. are commonly mistaken as negative reinforcement/pressure and release, when actually they involve the use of work being added as an aversive as a result of the horse refusing to do what is being told. For example, in barn sour horses, the horse is punished when he goes towards the barn because the aversive of working near the barn is added after the behavior of going towards it, in order to decrease the behavior of leaning or pulling towards the barn. It's easy to confuse negative reinforcement and positive punishment because in both techniques an aversive is used. If you are trying to increase behavior, the aversive is applied first and removed as reinforcement. If you are trying to decrease a behavior, an aversive is added after an undesirable behavior. To use negative punishment, you remove something pleasant as consequence for a certain behavior in order to decrease it. For example, if a horse becomes mouthy, sometimes leaving (i.e. removing your presence, something the horse finds pleasant since he thinks you are a chew toy) can be a form of negative punishment. The horse will learn that the behavior of mouthing and lipping at you causes you to go away, so he is less likely to continue the behavior. Not rewarding behavior can also be considered negative punishment. If the horse does not perform a behavior on cue, he will not receive a food reward and this in itself can count as negative punishment. Now that we have covered the quadrants of operant conditioning, I'd like to point out that negative and positive are being used from a mathematical perspective. Since operant conditioning was studied by scientists, they used these terms to denote the addition or subtraction of appetitives or aversives to the equation in the use of behavior modification. Negative does not mean bad and positive does not mean good- it means add or subtract. Reward based trainers use practically all positive reinforcement in their training. It is proven to be an extremely effective, stress free form of training. Without understanding the science behind clicker training, it can be hard to see how a click means anything to a horse in clicker training. The click is what is called a marker or bridge signal. It bridges the gap between the behavior you are reinforcing and the time it takes to deliver the reinforcement. Positive reinforcement can be used without a bridge signal, however a bridge signal has proven to be extremely effective at clearly communicating to the animal the exact moment/behavior that is being reinforced. For example, if you are teaching your horse to pick up the correct lead on the lunge line and he gets it right, by the time you get him stopped and reward him, he may think he is being rewarded for stopping, not picking up the correct lead. With a bridge signal, the trainer can mark the correct lead and the horse will know that is what he is receiving reinforcement for. So how does the horse know the bridge signal is marking a certain behavior?

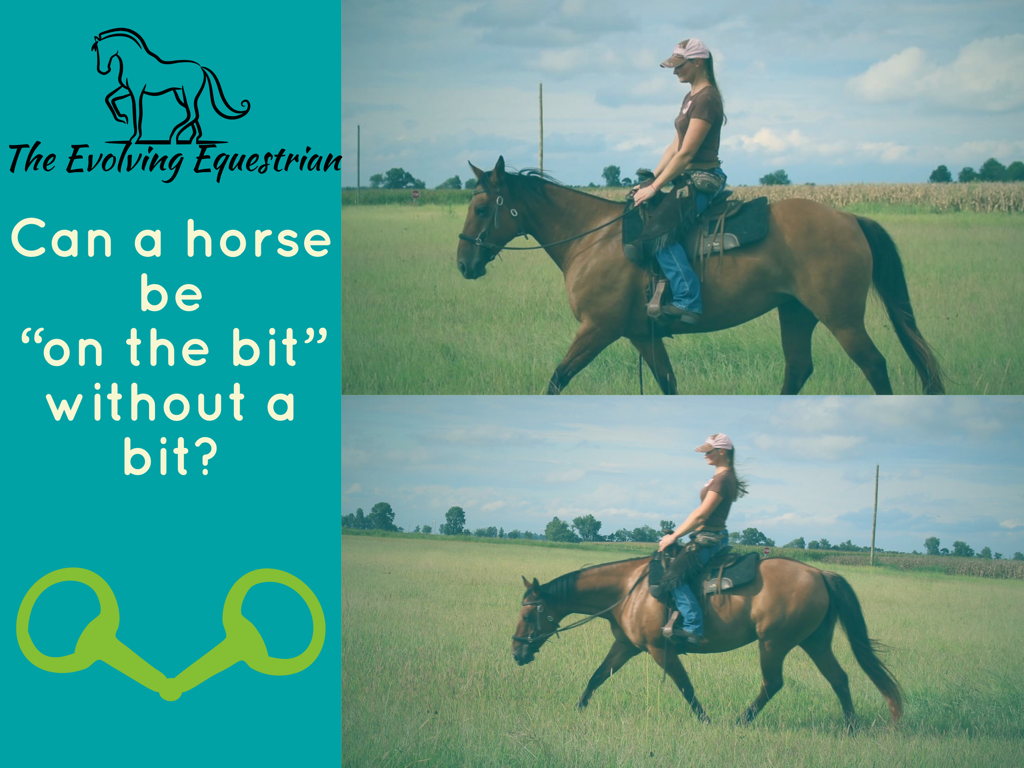

In the 1890s, Ivan Pavlov studied dogs’ response to food by salivating. With the dogs, Pavlov observed that they salivated before feeding them. He rang a bell before feeding them and eventually the dogs started drooling at the sound of the bell, because of its association with the food. What he discovered was that by pairing a neutral stimulus (bell ringing), something that could not itself illicit a response, with an unconditioned stimulus (food), something that produces an unconditioned or natural response (drooling) that eventually the neutral stimulus (bell) alone would illicit the same response as the unconditioned stimulus (food) and become a conditioned stimulus. With clicker training, we use a distinct sound like a click and pair it with food. In the initial stages when we condition the clicker, we click/feed, click/feed, click/feed. This is how we give the clicker value. It is how the horse knows that the bridge signal is rewarding him. When the horse hears the bridge signal, dopamine spikes. It’s part of the involuntary response produced by the clicker through its association with the food. Classical conditioning deals with involuntary responses where operant conditioning is made up of conscious decisions made by the learner. However, in training the two always overlap. The animal is always forming associations. In the above example involving the dogs, we the unconditioned stimulus (food) is an appetitive that creates a positive association, but classical conditioning works both ways, meaning it can involve aversives too and create negative associations. For example, if your saddle does not fit your horse properly and causes him pan, eventually the horse will shy away when you approach with the saddle. Many people don’t understand why their horse has developed a sudden fear of the saddle seemingly out of the blue. The saddle is a neutral stimulus, it does not naturally cause the horse to shy. However, pain is an unconditioned stimulus, it does naturally cause the response of fear and shying. Through pairing the two together the saddle and pain, eventually the sight of the saddle produces the response that the pain does. The horse has learned that the saddle predicts pain. In riding, we are taught to ask, tell, demand. This is classical conditioning as well. When we squeeze with our legs or point with the lead rope it is a neutral stimulus for the horse- it doesn’t produce a natural response. But when we pair it with a conditioned stimulus- pain/fear of pain by kicking the horse, using a crop, or swinging a stick and string that produce a natural response- move or run, eventually the horse forms the association that the squeezing or pointing means pain/fear and he will move/run when the neutral, now conditioned stimulus is presented. Whether you choose to utilize clicker training or not, it is important to understand classical conditioning because it is always happening whether you intend it to or even realize it. Without understanding how and why our horses are forming good or bad associations with various things, we cannot create the ones we want. If you ride bitless or have considered it, you’ve probably heard someone say that a horse cannot be properly trained without a bit. You’ve heard that a horse can’t possibly be “on the bit” if he’s not packing one around in his mouth. You’ve probably been told that a bit is required to advance your horse’s training to a higher level. Are these things true? Can your horse be ridden correctly without a bit?

While its easy to feel the pressure from other riders and trainers, it’s important to remember that you are on your own journey, doing what works best for you and your horse. However, you might be left wondering if any of these points are valid. You want to ride your horse correctly, and if this can’t be done bitless, you might be tempted to rethink your bridle choice. We know that behavior is altered by punishers and reinforcers. Bits do not possess some magical quality that modifies behavior some other way. With that being said, all a bit enables the rider to do is apply negative reinforcement or punishment easier. The idea that horses must have a bit to be trained correctly perpetuates the idea that it cannot be done without utilizing pain. And for those who know no other way, it’s easy to understand why they don’t think a bit is optional for proper riding. For those who know that responses can be trained through the use of appetitives instead of aversives, it’s clear that a bit is not necessary. Is it true that a horse cannot be “on the bit” without a bit? You may have heard already that the phrase “on the bit” does not exist in the classical texts from which it was translated. When the classical texts were translated from French to English, the phrase “on the bit” was created for lack of a better expression. It has been determined that a more appropriate phrase would be “on the aids”. Obviously, “on the bit” puts an unfortunate emphasis on the bit itself and the horse’s head and neck. From what we know of classical dressage, the focus is on the engagement of the hindquarters and connection over the horse’s back to create thoroughness, balance, and impulsion. This training deals in so much more than a bit or a single aid. The aim of dressage is to improve the natural paces. They become more beautiful with training. The horse develops pushing power and carrying capacity when brought along with the principles of classical foundation training. Focus on the hands and the bit has caused a downward spiral in modern dressage where we see horses being pulled into a false frame in attempts to get these horses “on the bit”. There is more to creating a responsive horse that seeks and accepts the aids than just pulling on the reins. If you take a look back at classical training, you will see that most of the schooling of the classical dressage horse was done in a cavesson. Eventually the bit was slowly introduced, and even still the reins were held in the left hand and were not used. This was done to preserve the sensitivity of the horse’s mouth. This would indicate that a horse can be properly trained without a bit. It wasn’t until much later in the training after the horse had been made light and in self carriage that the reins attached to the bit were held in the right hand. You can ride your horse correctly without a bit. If you are told otherwise, consider the source. They may not understand the principles of learning theory or the principles of classical dressage. |

AuthorChrissy Johnson shares her personal experiences and lessons learned training horses with reward based methods. Archives

July 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed